Hallo!

Here is a monograph from the ill-fated 'Wearing of the Gray" Confederate compendium, about to be given life in the forth-coming "The Civil War Musket.... 2nd Edition."

US MODEL 1841 PERCUSSION RIFLE

Harpers Ferry, Eli Whitney, Robbins & Lawrence, and Remington

The early 1840s were still the era of the big bore .69 muskets with longer (42 inch) smoothbore barrels, still being turned out with flint locks (1). The US Model 1841 was a true rifle, with a shorter barrel (33”) bored to a smaller caliber (.54). The earlier military rifles had 33 ½” or 32 5/8” long barrels. This same length barrels were used on rifles of European manufacture, hence the 33” barrel was the unofficial “industry standard” of the time period. The rifle had a shorter barrel, was in a smaller calibre and answered the need for a rifle for light infantry and for special purposes. The US 1841 was the first regulation U. S. muzzle-loading rifle made in the percussion system. The barrel had a fixed rear sight and no provision for a bayonet. The US 1841 was a handsome arm with a large brass patch-box in the stock flat, a brass side plate opposite the lock assembly and brass barrel bands with iron band springs. The internal lock parts were the traditional flintlock style, with a hooked mainspring bearing directly on the tumbler. (2) The barrel was browned (not “armory bright”), the lock plate was case hardened and the ramrod was trumpet shaped with a brass tip. The US 1841 rifles were smaller in dimension but not lighter in weight, and at 9 3/4 lbs they were almost a full pound heavier than the standard US 1861 rifle-muskets and actually a few ounces heavier than the much larger and longer US Model 1842 percussion muskets. The modern reproduction of the US 1841 is one of the few reproductions not substantially heavier than the original firearm. It actually weighs about the same. The nickname most often associated with the US 1841 was the “Mississippi Rifle” due to a Congressman from that state named Jefferson Davis. As a reward for Congressman Davis’s vote on a tariff bill, President James Polk arranged for the 1st Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (“The Mississippi Rifles”) that “Colonel” Jefferson Davis had recruited for the Mexican War to receive US 1841 rifles. Thanks in part to the effective fire of the 1st Mississippi regiment at Buena Vista, Mexico in February of 1847, Davis was able to hold back several attacks by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna on the American force and the Mexican army subsequently retired from the field. Davis, wounded in the action, returned home in June of 1847 to go on to become a senator from the state of Mississippi, Secretary of War, and later President of the Confederacy. Other period nicknames for the US 1841 rifle include “Harpers Ferry rifle,” “Whitney rifle,” “Jaeger rifle” variously misspelled as “Yaeger” or “Yager”, and “Windsor rifle.” This most-often nicknamed rifle produced by the three large government contractors (and the United States Harpers Ferry Armory) has an interesting and important role in Civil War history and one that used to be overlooked by the Civil War historical community.

Background

-Benjamin Robbins, 1747 (3)

As early as the First War for American Independence, General George Washington observed that the dress of the rifleman where possible must be maintained to “…carry no small terror to the enemy, who think every person a complete marksman.” (4)

While the major battles of the Revolutionary War of 1776 were fought on the East Coast very similar to European standards of engagement, the rifleman was quite different from the average American Colonist. While life in the Tidewater regions of the East Coast was almost equal to that in Britain, life on the plateau and mountains of the frontier was distinct. The individual frontiersman was required to defend his cabin, livestock, and cleared land from wildlife and hostile Indians. When combined with measures of self-reliance, independence, pragmatic brutality, hardship, deprivation, and a sense of democracy and familiarity with violence, riflemen were destined to have an impact in any war.

With the Contract Rifle of 1792, the U.S. Model 1803 Rifle, the Contract Rifles of 1807, 1814, and 1817, and the Contract Rifles of 1819 (Hall’s Patent), the day of the rifleman had arrived. With the advent of the new .58 “minie” rifle in 1855, adding greater effective firing range and accuracy to the rifle, advances and developments first begun by the British, French, and Americans during the Napoleonic War era led to (then) Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to look toward revisiting the “exercise and maneuvers” of troops acting as light infantry or riflemen. Davis was aware of the studies done in Europe to revise weapons and tactics, and appointed several officer boards to observe them and suggest changes to the U.S. system which was based upon the 1835 manual done by General Winfield Scott. Davis looked to Brevet Lt. Colonel William Hardee of the 2nd Dragoons who had studied tactics at the French cavalry school at Saumur in 1841, and where he had picked up French innovations regarding the value of rapid movement and deployment, the value of skirmishers, and hit-and-run style tactics by light infantry based upon French Legionnaire experiences in Algeria in the 1830s.

U.S. Model 1841 Percussion Rifle

While a number of the U.S. Breechloading Flintlock Rifle Model 1819 (Hall’s Patent) were converted to percussion, and the rifle updated as a percussion version in the form of the U.S. Breechloading Flintlock Rifle Model 1841, the decision to produce percussion rifles and muskets led to a new design in 1841. The US 1841 Rifle was stocked in hard oiled finished Pennsylvania grown American Black Walnut and brass mounted, weighing nine pounds twelve ounces, with an overall length of 48 ½ inches. The lacquer brown .54 calibre barrel was 33 inch long with seven grooves and a (slow) 1:72 inch twist. The 5 ¼ inch lock plate was flat with beveled edges, and the plate and hammer were color case hardened by quenching with the lock plate being inlet into the stock to bevel height. All furniture was polished brass, with the barrel secured by two band springs which held brass bands, the upper one being doubled looped and 2 9/16 inches long on top and 3 ¼ inches long on the bottom. Both straps are 15/32 inches wide. Screws and sling swivels were oil quenched blackened. The barrel carried the inspected, proofed, and acceptance (“V,” “P,” and “Eaglehead”) stamps, as well as a date usually that matched the lock plate date on the 2 1/16 inches long tang. Some contractor made barrels were stamped ‘STEEL.” The stock was marked with an inspector’s cartouche opposite the lock in the round or oval styles of the 1840’s or the square or rectangular styles of the 1850’s. A simple brass blade served as a front sight was set 13/16 inches form the muzzle, and the non-adjustable rear sight was a simple “v” notched block in the “Pennsylvania/Kentucky” rifle tradition. Surprisingly the sights were dead set for fifty yards. The brass trigger plate was nine inches long with rounded ends, holding a blued trigger on a lug. A separate brass trigger guard (bow) was attached with two spanner nuts. The 4 3/8 inch brass flat butt plate is stamped with a small “US” to the rear of the upper tang screw. The 32 ¾ inch bright steel ramrod and had a 23/32 inch long brass trumpet or flared shaped tip with a concave front for loading round balls. A “spoon” device in the stock channel secured the brass tipped ramrod.

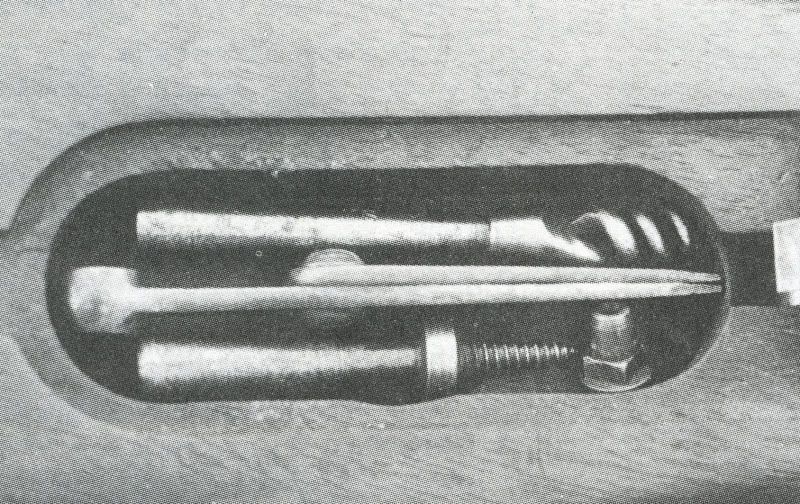

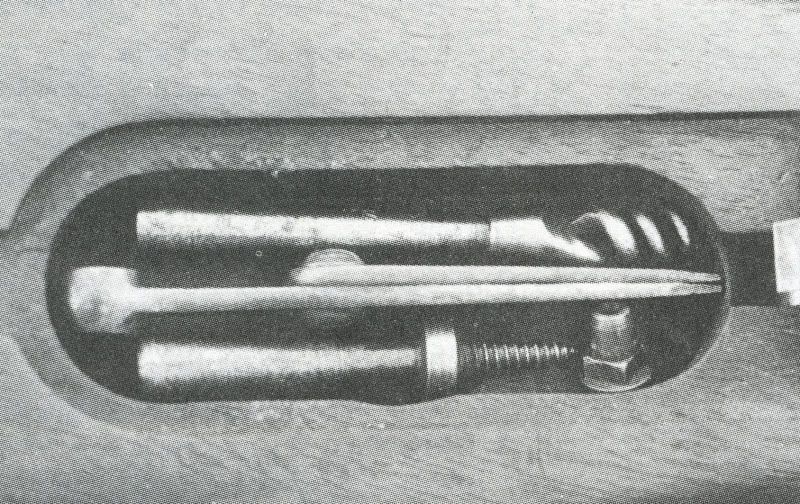

A distinctive feature of the US 1841 Rifle was its large brass “patch-box” or implement box that measured 7 5/8 inches by 1 11/16 inches. The bottom of the patch-box mortise typically carried one large very shallow circular cut centered with sometimes two others faintly visible on the side with a shallow hole in the centers, the remnants of the bit used to make the depth cut of the mortise. The bottom front end of the mortise was also drilled out to hold the space cone. Inside of the implement box were carried the three appendages that made up the US 1841 Rifle’s tools, on top a wiper with a long shaft, in the center the US 1841/1842 Combination tool (cone wrench with a single screwdriver arm), and on the bottom a ball screw on a shorter shaft to allow it to fit next to the cone. When all three tools and spare cone were carried, there was little room for anything in the box. Most tools were contractor made and were japanned black or oil quenched blackened carrying stamps such as “S,” “M,” or large “US.” Springfield and Harpers Ferry made tools have a grayish blue finish and have a small ‘US” stamped on them.

There was no provision to mount a bayonet, and at times the rifle was augmented by the M1836 Hicks or the M1849 Ames “Rifleman” knife. The lock plate was stamped with the name of the maker in one or two vertical lines over the year to the rear of the hammer, and for those made at Harpers Ferry Armory, a spread eagle and “U.S.” to the front of the hammer. The US Model 1841 percussion rifle used a cartridge containing a pre-patched .535 round ball and 75 grains of powder. The US1841 Rifle would have a profound influence on the new .58 calibre Model 1855 rifle, which incorporated both the new .58-minie bullet as well as the Maynard tape primer system. The first two variations (of five) of the US 1855 Rifle, made in 1857 and then modified in 1858, were brass mounted like the US 1841.

In addition to the 1st Mississippi, the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, organized during the Mexican War also carried the US 1841 rifle in Mexico and later on their march from Fort Leavenworth to Oregon along with Colt revolvers and some Maynard carbines. Production of the US 1841 rifle did not begin at the US Armory until 1846 when 700 were turned out at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Between 1846 and the end of production in 1855, 25,296 rifles were produced at Harpers Ferry. There is some controversy over production at Springfield Armory divided between camps that there are no records indicating any production of US 1841 rifles and others that 3,200 were produced in 1849. Springfield records are somewhat unclear, and the 3,200 referenced in the “3,200 arms” would appear not to be US 1841 rifles but rather shortened US 1842 muskets altered for the Fremont Expedition. However, from time to time, US 1841 rifles are found with Springfield marked lock plates (see pictures). While some argue these are actual Springfield produced US 1841 rifles, others believe that these rifles were refurbished or retrofitted with Model 1847 Musketoon locks or lock plates which are close to identical to the US 1841 lock. It is worth noting that any US 1841s produced at Springfield Armory would be exceedingly rare whatever the case, as Springfield did not produced muzzle-loading rifles like the US 1855 either, only the longer three band rifle-musket. Harpers Ferry Armory made the US model rifles. The reasons for this division of manufacture are not documented.

"Steel" stamped barrel:

A Look at US 1841 Percussion Rifle Armory and Contract Alterations

HARPERS FERRY ARMORY

In the mid-1700s Robert Harper, a millwright formerly from near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania moved to Virginia and operated a ferry service across the gap in the Blue Ridge where the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers converge. In 1763, the Virginia General Assembly established the town of “Shenandoah Falls at Mr. Harper’s Ferry.” In 1796, the Federal government purchased the 125-acre parcel of land bounded by the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers from the heirs of Robert Harper. Construction of the "United States Armory and Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry" began in 1799. Three years later full-scale production of arms began. Muskets, rifles and, after 1805, pistols were all manufactured here. Total production until the outbreak of the Civil War (and abandonment of the Armory) exceeded 600,000. (5)

Captain John H. Hall, beginning in 1819 built the Hall Carbine at Harpers Ferry on the principle of interchanging parts and using an assembly line process. The Hall Carbine had a removable breech section and lock unit. When the Federal government adopted the Hall Carbine, the United States became the first nation to employ a breech-loading weapon as a “standard” military arm. Originally produced in flint, the Hall Carbine evolved into a percussion version as well and remained in service for almost fifty years.Harpers Ferry also produced 25,296 US Model 1841 Percussion rifles at the Armory between 1846 and 1855. There is no evidence that the US 1841 was produced at Springfield Armory. The period nickname for the US 1841 of “Harpers Ferry Rifle” is somewhat confusing as the US Model 1855 two-band rifle shared the same nickname in period accounts.

The Harpers Ferry US Model 1841 barrels are marked with a “VP” and eagles head at the rear of the breech, and besides lock plate markings are distinct for having no cartouches opposite the lock. The initials JLR or JHK often appear in block letters in the area where the cartouche would be expected. The patch-box has three small router holes and no “U.S” initials on the butt plate. (6)

US 1841 “Harpers Ferry Rifle”

Harpers Ferry Alterations

The Americans were not entirely without vision when it came to the concept of the changing round ball being looked at in Europe by some men as with Delvigne, Pontchara, Thierry, Thouvenin, and Minie in France, Augustin in Austria, and Metford, Pritchett, and Wilkinson in Britain. Between 1853 and 1855, at Harpers Ferry and Springfield Armories, small arms projectile tests were conducted. In late 1853 Colonel Benjamin Huger was authorized by the Ordnance Department to conduct tests at Harpers Ferry. Tests of the Minie system led to James Burton, acting Master Armorer at Harpers Ferry, to come up with different ideas for expanding the base of the conical ball to grip the rifling of a barrel.. A prototype .69 and .54 bullet based upon the Minie design was chosen. Additional experiments were ordered done at Harpers Ferry in October of 1854 under Lt. J. G. Benton based upon the Pritchett bullet. Another series of tests under Benton were authorized in the spring of 1855 at Springfield Armory. After the tests, Colonel H. K. Craig recommended to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis that a new bullet in .58 calibre be proposed for small arms. The proposal was accepted by Davis in July of 1855, and Davis called for the establishment or alteration of a .69 rifle-musket altered from smoothbore, a new .58 rifle-musket, a new .58 rifle, an altered M1841 rifle from .54 to .58, and a new .58 pistol-carbine. The M1855 Carbine, authorized in 1854 in .54 would also be updated to .58.

Somewhat anticipating the development of the new bullet, in late 1854 and early 1855, Harpers Ferry re-tooled the M1841 Rifle as its potential for long range firing with the new .54 “minie” ball was hampered by its limited fixed sights. 9,800 M1841 rifles were altered by Harpers Ferry to fire minie ball ammunition. Several variations are known, the key differences being .54 or .58, and several different forms of the long range rear sight graduated to 900 or 1,000 yards- one a slightly larger version that was soldered to the barrel and the other the M1855 Rifle long range rear sight that was dovetailed and screwed to the barrel. With the advent of the short-range M1855 Rifle rear sight in late 1858 graduated to only 100, 300, and 500 yards, Harpers Ferry altered M1841’s carried the new rear sights. In late 1854 and early 1855, Harpers Ferry Armory altered 1, 631 rifles to take the new “screw” long range rear sight designed by Benton and 1,649 rifles to take the 1,000 and 900 yard high-hump or “roller coaster” sliding pattern ladder rear sights. These long range sighted US 1841 rifles were also modified to accept sword bayonets typically by replacing the long front band/nose cap with a shorter version, replacing the brass front sight blade with an US 1855 Rifle front sight, adding an US 1855 bayonet lug to the barrel for either a special “US 1841” type sword bayonet or the US 1855 Rifle sword bayonet, and replacing the flared concave faced brass tipped ramrod with an all iron/steel one with a tulip type cupped head. With the adoption of the .58 minie bullet in July of 1855, the Armory reamed the bore from .54 to .58 as well. About 1,646 "Snell" type bayonets were produced at Harpers Ferry in 1855 that used a rotating thumbscrew type lock that required two small cuts on the side of the barrel to engage. Between 1855 and 1857 Harpers Ferry produced 10,286 sword bayonets to be used with a more conventional side mounted lug, but these required that the M1841 rifle stocks be cut back slightly and a shortened upper band fitted. Later, a third type of bayonet was produced under contract that required no alteration to the rifle, only the addition of a bayonet lug that clamped in place. The presumption has been that a comparable number of rifles were altered for the bayonets in the context of enlarging the caliber, but that is not the case. The numbers do not jibe. In 1855, the first of the altered M1841’s were issued to the 2nd, 6th, and 10th U.S. Infantry. Some of these altered rifles were issued to Regular infantry regiments as early as 1856, followed by the largest issuances of 5,600 altered rifles in 1858 to the Artillery, and Mounted Rifles, and Dragoons at various posts.

ROBBINS & LAWRENCE

Samuel Robbins and Richard Lawrence came to the gun trade much later than either Eli Whitney or Remington, and left sooner. Located on the Connecticut River in an area known as “Precision Valley” for the amount and quality of machine tools, Robbins and Lawrence entered into a partnership with Nicanor Kendall building rifles at Windsor Prison in 1844 actually employing prisoners as cheap labor. Probably realizing the risks and limitations involved with making and storing firearms in a prison, the partners built a large brick factory two years later in 1846. Frederick Howe was then the factory superintendent. Howe, who would later be hired away by Providence Tool, invented several new milling machines and lathes for the making of interchangeable gun parts by Robbins & Lawrence. Their first contract with the US government was to produce copies of the US Model 1841 percussion rifle. The very first US 1841s produced by the firm on contract were marked with all three names, Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence. These have the earlier lock plate dates. After 1847 when Nicanor Kendall left, the firm changed names and the locks were simply marked Robbins & Lawrence over US, with the date and WINDSOR behind the hammer (7). The barrel flat on the Robbins & Lawrence US 1841 was not marked STEEL, as were all the Remington and some of the Whitneyville variants. The government US 1841contracts totaled 25,000 US 1841 rifles and all were delivered by 1855.

Robbins & Lawrence received global attention in England at the 1851 Crystal Palace exhibition (a "World's Fair" of sorts). Their display was very simple, consisting of six rifles which were disassembled and reassembled to demonstrate interchanging of parts. At the time military arms in Britain were hand-made from parts not likely to

interchange with another gun, much less six others. The British government took note, and sent a commission to Windsor, VT resulting in a major contract for Robbins & Lawrence to supply 25,000 (type 2) P-53 Enfields to the Crown during the Crimean War as well as machinery and tools for the refurbishing of the Royal Small Arms Manufactury at Enfield Lock (8). The British contract proved their undoing. Plagued by production problems from the beginning and burdened by debt from re-tooling, Robbins & Lawrence could only deliver 10,500 on the original P-53 Enfield contract by September 1856. By then the Crimean War was over, and the British foreclosed on the contract (9). In addition, the company had recently lost over $100,000 (a princely sum in those days) on a bad investment building railroad cars. Robbins & Lawrence were forced to liquidate their assets. Ironically, Colt, Eli Whitney and LG&Y were all beneficiaries purchasing manufacturing equipment and machinery that they later used to produce contract rifle-muskets during the Civil War for the Federal government (10). Robbins & Lawrence US 1841 rifles were mostly stored at Watertown Arsenal near Boston prior to alteration.

US 1841 “Windsor Rifle” (Robbins & Lawrence) here shown with later alteration that included an M1855 "short range" rear sight:

WHITNEYVILLE

The private Armory, as Whitney called it, was divided into two main facilities on opposite sides of the Mill River. On the East side was the facility for the shaping of metal parts and on the west bank was the machinery for the cutting of parts and shaping of wood (11). Eli Whitney passed away in 1825, and some time later as previously stipulated his only son, Eli Whitney, Jr. took over the operation of the Whitneyville Armory. The first government contracts procured by Eli, Jr. were for the “new” US Model 1841 Percussion Rifle, actually four contracts from 1842 to 1854, for a total production of 22,500.

The Federal contracts specified “parts interchangeability” and the US government performed random inspections on each shipment to determine if the rifles were military gauged. Many were not accepted and by the mid-1850s Whitneyville found itself with a large inventory of “reject” parts. Whitney preferred state contracts, which were not subject to inspection with gauges (12). Whitneyville also produced commercial US 1841s out of condemned and surplus parts from Springfield and Harpers Ferry which were sold to state militia. The Whitney Militia Rifle is a hybrid between a US 1841 rifle and a Model 1855 rifle with a “hump” type lock plate, minus the patch-box, tape primer and using a Maynard type hammer. Two types of the Militia Rifle were produced with the main difference being the location of the rear sight. Type I has a ladder type long range sight located 2 7/8 inches from the breach while the Type II has the sight about 6 inches down the barrel.

Whitney is most famous for what was termed “good and serviceable arms not subject to government inspection of gauges” an interesting strategy for the enterprise that started the whole “American Plan” of parts interchangeability. The civilian and to an extent the state militia markets did not support the need for strict interchangeability of parts, as long as the rifles were functional and would fire reliably. However, Whitneyville’s use of condemned parts (the Armory would strike over the government condemnation marks) to fob off guns of lesser quality to unsuspecting buyers is in contrast to the efforts of other U.S. commercial gun-makers. To Whitney, the cheapest route was always favored.

The US 1841 rifles were generally marked “E. Whitney”over “US” with “N. Haven” and the date behind the hammer (13). The barrels were sometimes marked STEEL on the barrel flat. They were also sometimes marked “U.S.” over SK, GW, JH, JCB, JPC, or ADK over VP. There were two cartouches opposite the lock.

US 1841 (later contract) made by Whitney, use by Colt for his alterations. Note Colt M1855 Revolving Rifle rear sight.

E. REMINGTON & SONS

E. Remington and Sons began in 1816 as a sporting gun barrel maker in the Mohawk Valley of New York state. In 1828 the operation was moved to the banks of the Erie Canal near Ilion, New York. Remington was one of the first gun-makers to use steel in their barrels, which were highly sought after (14). The strategy changed when Remington began buying out the contracts of Federal military suppliers who behind on their shipments and completing them at their factory. The second government contract for Remington was the US Model 1841 rifle. The Ordnance department was impressed by the quality of the initial deliveries of these rifles, and extended a total of four contracts totaling 20,000 units from 1846 to 1855. The barrel flat on the Remington is stamped STEEL, the lock plate reads REMINGTON’S over HERKIMER over N.Y. with the date and US behind the hammer. All of the Remington contracts were delivered as agreed, and few if any were rejected. Remington usually referred to the US 1841s in correspondence as “Harpers Ferry rifles.” After 1855 the US Model 1841 evolved into a newer version, in the “standard” .58 to take advantage of the new Burton designed minie bullet. Remington was given a government contract to ream out the barrels of the older .54 US 1841s (to .58), and fit them with bayonet lugs. Unlike Whitneyville Armory, Remington did not supply contract arms to the southern states after the start of the US Civil War in 1861.

Interestingly, when the US Civil War began E. Remington & Sons did not capitalize on the new Federal and State rifle-musket contract work like Whitneyville and others. Remington did enter into one “regular model” US 1861 rifle-musket contract on August 20, 1862 but they made no deliveries on it (15). Instead, having all the machinery on hand from the earlier US 1841 contracts, Remington agreed to make 12,500 modified 1841 rifles in .58 with bayonet lugs. These are referred to variously as the Remington 1862 contract rifle, or 1863 contract rifle, depending on the contract or the delivery date. The Remington rifle was similar in appearance but entirely different in detail from the US 1841 Percussion rifle. By the time the final deliveries were made, in December 1863, the Ordnance department was no longer as desperate for any infantry arms they could procure. There was some reluctance about issuing the Remington rifles as replacements for rifle-muskets, and they were apparently stored until the end of the war and sold off as surplus along with at least a million other infantry arms. There are no records of any Remington 1863 contract rifles issued to any troops during the US Civil War (16). Presumably, these rifles were stored in Watervliet Arsenal, as that is where the US 1841 percussion rifles made by Remington were also stored prior to alteration and issuance.

US 1841 Remington contract

Part Two

CONFEDERATE VERSIONS and POST 1855 ALTERATIONS

Southern Use of US 1841 Rifle

One reason a shortage of rifles in Northern armories and arsenals in 1861 at the outbreak of the Civil War was that after ordering an inventory made of muskets and rifles held in Arsenals and Armories in 1859, in December of that year Secretary of War John Floyd had ordered the Chief of Ordnance to send 10,000 .54 calibre percussion rifles to several Southern arsenals from the 43,375 total reported by Colonel H. K. Craig. 2,000 US 1841 rifles were delivered to the arsenals at Fayetteville, NC, Charleston, SC, Augusta, GA, Mount Vernon, AL, and Baton Rouge, LA to boost their limited inventories. When the Southern armories and arsenals were taken over by the Confederates, they received a boost in .54 calibre US 1841 rifles, and some of the 3,570 newer .58 US 1855 rifles held at Harpers Ferry Armory. Many were not destroyed by the fires or assembled from a limited number of semi-finished and parts that could be salvaged from the rifle works facility in numbers overly reported as destroyed by the Harpers Ferry commander and overly reported as captured and assembled by the Confederates. It should be perhaps noted that of the 15,060 US 1841 Rifles inventories in armories and arsenals in the South, only 1,385 were altered from .54 to .58 calibre.

The Patchbox

Shows the spare cone and tool, but is missing the wiper and ball screw.

Another showing typical mortise:

A look at the appendages in place. It is unusal to find them there, as they normally have been lost in time, or sold separately for greater profits.

The rifled military arm was far from a new design at the time of the US Civil War. The smoothbore musket still predominated as military arms because of the difficulty in loading a rifled infantry arm quickly or repeatedly. In order to be effective, a rifle required a tight fitting projectile to achieve the necessary compression and take the spin affording by the rifled barrel. The problem was that once the barrel heated up, the tight fitting bullet no longer loaded as quickly or easily. Early military rifle designs like the British Baker rifle (beginning around 1800) were sometimes issued with a mallet to hammer home the ball once the bore heated up. Taking a practical feature from the frontier, it was discovered that a slightly smaller bullet wrapped in a greased patch rammed home much more easily. The use of the patched round ball also gave rise to one of the distinctive characteristics of the frontier hunting rifle, the patch box on the rifle stock. In the patch box one could easily store a supply of greased patches (or grease) and keep them free of the dirt and contaminants that would normally stick to such a material stored elsewhere. It also held various necessaries such as tools, spare flints or a spare cone if the rifle had a percussion lock. The patch box is still a feature found on flint and percussion “American mountain” (1) black powder hunting rifles, but in terms of any military application it proved short-lived.

A number of inventors had already devised self-expanding bullets when, in 1836, Birmingham gun-maker William Greener developed such a bullet consisting of a flat-ended oval ball with a cavity in which a metal plug was inserted. When the gun fired, the plug drove forward and caused the bullet to expand and engage the rifle grooves. Greener submitted his invention to the British government, but it was rejected; a short while later, when a French captain, Claude Minié, received £20,000 from the British government for a similar bullet, Greener sued the Ordnance Department for patent infringement and was ultimately awarded £1,000 by the court. It is not certain how he prevailed in the claim for damages given the apparent differences in design, but Greener was not one to be shoved around by anyone, including potential customers the size of the Ordnance Department. (2) Regardless of the outcome of the case, the famous rifle-musket round that produced so much carnage and shattered limbs during the US Civil War was forever afterwards called the “Minié ball” and not the “Greener bullet.” And with that particular enhancement in ballistics, the patch box gradually began to disappear from the design of newer rifled military arms.

The United States was quick to adopt and improve upon the new ballistics technology (3) but with a nod to its frontier heritage, it was slower to adopt the new trends in military arms design, particularly where elimination of the patch box was concerned. The US 1841 Percussion rifle had a large brass patchbox in the stock. The Maynard tape primer US 1855 rifle still had a patch box when it began production in 1857, as did the last generation of the US 1855 rifle-muskets (3 band) that were in production through mid-1861. Strong consideration was given to a continuation of the patch box for the new US 1861 rifle-musket, and a proto-type version with a round lid was proposed but never produced. The following account lends insight into the discussions which occurred during in 1860, just prior to the Civil War:

"From the best information the board can obtain from officers using the rifle musket it appears the patchbox is very convenient and useful for carrying a greased rag or grease. The report of inspectors general indicates that the same difficulty has been found in our service that has been reported in the British service in India with regard to the drying up of the grease used in the cartridge as a lubricator for the bullet of the rifle musket; and as the use of a lubricating material is very important for accurate shooting with these arms, the Board is of the opinion that the patchbox should be retained, and they recommend the adoption of the pattern presented from Springfield Armory (marked A 117) as the neatest and cheapest plan offered.

Major Hagner desires to record his dissent to the above recommendation...the arm fabricated for the general service should consist of as few parts an be as little costly as possible to fit for effective service. The patchbox in the stock is costly and cannot be of general use in the ranks as grease...renders the arm untidy to handle if so used. Should marksmen on special service in deliberate firing find it best to have an additional supply of grease on hand it can be carried with equal convenience in a box detached from the gun and of little cost. The patchbox has not been applied to the rifle musket in any European service, as far as known to me although the cartridges used by them are not superior to our own." (4)

Ultimately, the exigencies of the US Civil War and demand for small arms dictated that cost and additional production time necessary to add a patch box was no longer desirable, at least on US model rifle-muskets. The projectile or (for the Enfield) the cartridge paper itself was lubed instead. The patch box was still found on commercially made military rifles of proprietary design (5), such as the Sharps rifle even though they were breechloaders with no need of a greased patch.

US 1841 Sword Bayonets

The original US 1841 Percussion rifles were not designed for use with a bayonet. With the modernizing efforts of the mid 1850’s, it was decided that the altered US 1841 rifle were to be made to accept a sword or saber bayonet as would be done for the new forthcoming US 1855 Rifle. Initially, an experimental sword bayonet was produced for Harpers Ferry and Eli Whitney alterations that mounted on a lug that had a narrow one-inch long guide rail. The bayonet design was slightly altered to eliminate the guide rail. When the new sword bayonet came out for the US 1855 Rifle, it would also fit on the altered US 1841 Percussion rifles. In addition, sword bayonets were supplied for some of the alterations by contractors such as Collins & Company. As a result, there are several slightly different hilt and blade profile examples of “US 1841 sword bayonets.” Perhaps the most unique was the “Snell” pattern turnbuckle sword bayonet used in conjunction with the first of the 590 US 1841 alterations using the Benton “Screw” rear sight made at Harpers Ferry between 1854 and 1855. The “Snell” bayonet featured a sliding clamping ring with the muzzle of the barrel being milled on the one side with a 1/16 inch and a 3/32 inch deep groove. The Benton rear sight proved a failure, and the next 1,041 rifles featured the early US 1841 sword bayonet with the one-inch guide rail.

Southern Copies of the US 1841 Rifle

As battles were fought and won, the opportunity for captured and refurbished Federal arms provided arms of all kinds. It was perhaps only natural that the popularity of the U.S. 1841 and British Enfield (P53, P58) would lead to its use as a pattern for Confederate produced rifles and rifle-muskets. The US 1841 was often copied varying only in a simplified the front band or omitting the patch-box. Confederate firms and Armories that produced rifles patterned after the US 1841 Percussion rifle were: Asheville, NC Armory, M. A. Baker of Fayetteville, NC, C. Chapman (possibly from Tennessee), Clapp, Gates & Co. in Whitsett, NC, Davis & Bozeman of Alabama, Dickson, Nelson & Co. of Dickson, AL, Gilliam & Miller, H. C., Lamb & Co. of Jamestown, NC, Mendenhall, Jones & Gardner (“M.J.& G”) of Whitsett, NC, J. P. Murray of Columbus, GA, L. G. Sturdivant of Talladega, AL, an unknown maker in Tilton, GA, and an unknown maker that was possibly Searcy & Moore of NC. Most of the contractors delivered fewer than 1,000 finished arms and sometimes only a few hundred arms before the end of the war.

CIVIL WAR PROVENANCE

Due to the unprecedented numbers of Confederate regiments formed in 1861 and the need to be uniformed, equipped, and armed, most infantry regiments followed the time honored model of issuing the two flanking companies in a regiment with “rifles” whenever possible. These rifles were issued for flanking, scouting, and skirmish work while the remaining eight companies remained armed with smoothbore muskets, rifled-muskets, or an increasing number of captured US model, Richmond or other CS Armory and P53 rifle-muskets. Of course, the arming of individual units was often piecemeal and haphazard depending on time and theater of war, as well as what was available. Initially, few units formed in the South were fortunate to receive a full complement of “First Class” arms of the latest models and some volunteer units began the war flintlocks arms donated or brought from home.

From Richmond on May 3, 1862 General Robert E. Lee replied to a request:

Compared to Brigadier General J. S. Marmaduke’s May 20, 1863 report:

However, depending upon the unit, time, and place, it was not unheard of to find units entirely equipped with rifles especially after imports through the Blockade and Confederate manufacture started to catch up with demand. Including the 25,296 rifles produced by the US Armory at Harpers Ferry, and various other small contractors up until 1855, there were a significant number of US 1841s on hand in various state arsenals at the onset of the US Civil War (19). Secretary of War John Floyd directed the Ordnance department to move 115,000 small arms (including over 10,000 US Model 1841 rifles) to southern arsenals. In 1861, fully twenty years after the model was designed the US Model 1841 Percussion rifle was far from obsolete. The Federal ordnance department issued them to US troops early in the war, but replaced most of the1841 rifles with the standard US 1861 rifle-muskets as they became available. However, these rifles were still seeing action with Confederate infantry years later. In the Confederacy, the existing stockpiles of US 1841 rifles and Confederate copies were widely used. There were over 15,000 US 1841 rifles in Southern Arsenals at the beginning of the Civil War. CS contractors continued to produce more as the war progressed, and several common CS contract rifles were copies of the 1841.

Confederate infantry units issued the US 1841s include the 18th Georgia; 18th and 21st Mississippi; 1st and 7th Tennessee; 4th , 6th , 9th, and 23rd Virginia; and the 3rd, 8th and 15th South Carolina. In terms of battle engagements, the 9th Virginia participated in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, and carried their US 1841s to the “high water mark of the Confederacy” with General Lewis Armistead on Cemetery Ridge the afternoon of July 3, 1863. In the western theater, Confederate field inspection reports for May 1864 show that Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry was armed with nearly 2,600 “Mississippi rifles,” using them at Brice’s Crossroads and elsewhere. Some other Confederate cavalry regiments issued these rifles included: the 18th and 19th Mississippi; 8th, 11th, and 23rd Texas; and the 12th and 14th Virginia (20).

Initially, 90% or at least the overwhelming majority of Confederate that were issued US 1841 rifles were the original configuration, .54 calibre versions made with no provisions for a bayonet. This was due to the Arsenals in the South having primarily unaltered versions in storage, hence these were subsequently the arms first seized by Confederate forces. The exact number supplemented by the later addition of sword bayonets through clamping adaptors cannot be completely determined. Nor are the exact numbers known of US 1841 alterations made between 1854 through 1862 with .54 or .58 bores, long or short range sights, US 1855 Rifle front sights, and bayonet mounting lugs falling into Confederate hands due to capture or battlefield pick-up. Certainly any serviceable US 1841s would have been popular swaps for any soldiers “Wearing the Gray” and still toting smoothbore flintlock conversion muskets.

The original US 1841 rifles were all (more or less) uniform in their basic configuration with a fixed rear sight, .54 caliber bore, and no provisions for any type of bayonet. As discussed previously, by the Civil War-era most US 1841s had been moved out to various state arsenals. There were two or three "Federal" conversions done at different arsenals or under commercial contract between 1855 and 1861 that had some degree of consistency. Besides those, large numbers were converted by the various states, or perhaps even militia units, which had the arms in their possession. Alterations usually consisted of some provision to take a socket or sword bayonet; the addition of adjustable sights; and the conversion from .54 to .58 caliber. Federal alterations began as early as 1855 when the .58 caliber “standard” was adopted. An order on July 4, 1855 directed that the Model 1841 rifles were to be increased in caliber (to.58), fitted with sword bayonets and long-range rear sights. However, despite the alterations and upgrades are found in a wide variety, the number of which almost defies analysis some patterns emerge. The following capsule summaries are presented with an informal alphabet typology used here for reference and clarity. The “base model” is of course the original configuration for the US 1841 percussion rifle.

Base: The U.S. 1841 Percussion Rifle

1. .54 calibre barrel

2. long double loop front band

3. ¼ inch tall ‘Pennsylvania/Kentucky” rifle type simple block rear sight

4. 5/16 inch tall brass blade front sight

5. tapered concave faced brass tip ramrod

6. no provisions for mounting a bayonet

Variation A: The US 1841 Experimental Model done at Harpers Ferry

1. .54 calibre barrel

2. 1854 short double loop front band (1 ¾ inches long on the top)

3. M1842 long range rear sight with a length of 2.25 inches and a height of .706 inches, graduated to 800 yards soldered in place

4. original M1841 brass blade front sight

5. early M1841 sword bayonet lug with one inch guide rail

6. iron/steel tulip shaped tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 ½ inches from the breech, sight radius 27 ½ inches, 5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation B: The US 1841 with US 1842 alteration long range rear sight done at Harpers Ferry

1. .54 calibre barrel

2. short double loop front band

3. M1842 long range rear sight with a length of 2.25 inches and a height of .706 inches, graduated to 1,000 yards soldered in place

4. original M1841 brass blade front sight

5. early M1841 sword bayonet lug with one inch guide rail

6. iron/steel tulip shaped tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 1/2 inches from breech, sight radius 27 1/2 inches, 5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation C: The 600 US 1841 Whitneyville with US 1855 Rifle long range rear sight

1. .54 calibre barrel

2. short double loop front band

3. M1855 Rifle rear sight graduated to 1,000 yards soldered in place

4. original M1841 brass blade front sight

5. early M1841 sword bayonet lug with one inch guide rail

6. iron/steel tulip shaped tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2.875 inches from breech, sight radius 26.5 inches, 5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation D: The US 1841 with the US 1855 long range rear sight graduated to 500 yards on the sides done at Harpers Ferry

1. .54 or .58 calibre barrel

2. short double loop front band

3. M1855 Rifle rear sight with a length of 2.470 inches and a height of .750 inches, graduated to 900 yards but with sight sides graduated to 500 rather than 400 yards soldered in place

4. M1855 Rifle front sight

5. M1855 sword bayonet lug

6. iron/steel tulip shaped tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2.5 inches from breech, sight radius 27.5 inches,

5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation E: The US 1841 with US 1855 (1858) short range rear sight done at Harpers Ferry

1. .58 calibre barrel

2. short double loop front band

3. M1855 Rifle (1858) short range rear sight graduated 100-300-500 yards dovetailed and screwed to the barrel

4. M1855 Rifle front sight

5. M1855 sword bayonet lug

6. iron/steel tulip shaped tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 7/8 inches from breech, sight radius 28 ¾ inches, 5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation F: The 11,368 US 1841 Colt alterations done at the Colt factory

1. first production .54, subsequent production .58 calibre barrels

2. original long double loop front band

3. Colt M1855 Revolving Rifle fold-down rear sight dovetailed to the barrel

4. original M1841 brass front sight

5. Colt pattern clamp-on ring bayonet lug mount

6. iron/steel tulip tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 15/16 inches from breech, sight radius, 5 inches muzzle tip to muzzle

Variation G: The 1,742 US 1841 alterations modified by A. J. Drake for the State of Massachusetts

1. .54 calibre barrel

2. original long double loop front band

3. M1855 Rifle short range rear sight with the angled rear of the sight base filed flat to 90 degrees without the dovetail extension angle dovetailed and screwed to the barrel

4. M1855 Rifle front sight which serves as the bayonet stud for an interior diameter modified M1855 socket bayonet

5. iron/steel tulip tip ramrod

6. base of rear sight location 2.85 inches from breech, sight radius 28.5 inches, 5 inches stock tip to muzzle

Variation H: The 590 US 1841 alterations with first bayonet configuration done at Harpers Ferry

1. .54 or .58 calibre barrel

2. original long double loop front band

3. Benton “Screw” pattern adjustable rear sight dovetailed to the barrel

4. original M1841 brass front sight

5. muzzle end of barrel milled with two slots for the Snell pattern sword bayonet

6. iron/steel tulip tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 7/8 inches from breech, sight radius 28 7/8 inches, 5 inches stock tip to muzzle

The Benton “Screw” pattern rear sight was not a success when used in the field, so the M1841 rifles milled for the Snell bayonet were later returned and a 17/32 inch high simple block rear sight replaced the Benton rear sight.

Variation I: 1,041 US 1841 alterations with the second bayonet configuration done at Harpers Ferry

1. .54 or .58 calibre barrel

2. short double loop front band

3. Benton “Screw” pattern rear sight dovetailed to barrel

4. original M1841 brass front sight

5. early M1841 sword bayonet lug with one inch guide rail

6. iron/steel tulip tip ramrod

7. base of rear sight location 2 7/8 inches from breech, sight radius 28 7/8 inches, 5 ¾ inches stock tip to muzzle

The Benton “Screw” pattern rear sight was not a success when used in the field, but only the Snell bayonet alterations were retuned to replace the Benton rear sights.

Summary

Aside from the rifles secured by the Confederate seizing of Federal Armories and Arsenals in the South, the partial reliance by the Confederacy on arms captured or taken from Federals on the battlefield provided a real resource. The Confederate Ordnance efforts were bolstered with recycled serviceable arms and to the extent possible sometimes repaired and refurbished arms for reissue. Through capture and battlefield pick-up many unaltered and altered US 1841 Percussion rifles entered Confederate service.

In 1864 as more and more regiments turned in their still serviceable US 1841 rifles for the Union Army’s standard versions of the US .58 rifle-musket, increasing numbers of them went into storage at either the various Arsenals or storage depots. Already by February 1864, their number had risen from 5,900 in December to 8,700. By February of 1864, 650 were stored at the New York Arsenal, 1,582 at the St. Louis Arsenal, 1,740 at Vancouver, and 2,186 at Washington Arsenal. By June of 1864, only about a dozen units were reporting US 1841s in their possession. In addition, with the Civil War’s end in April of 1865 in the eastern theater, it was reported that Union troops took home officially at least, 146 Whitneyville, 11 Windsor, and 15 Harpers Ferry produced US 1841s for use as hunting rifles or perhaps souvenirs. In the post-bellum environment of breechloaders, .54 and .58 calibre US 1841s were largely assigned to storage or disposal, with some very few being assigned for other military purposes. Some of the rifles were sold to the public in the 1870s for $4.00 each, but by the 1880s that price had dropped to $1.50, then to $1.00, and down a low of 50 cents. Disposal efforts reached a peak between 1875 and 1889 when the various Federal Arsenals sold off the remaining US 1841s, the resolute veteran of both the Mexican and US Civil War(s).

Notes

1. The last military musket in flint was the US Model 1835 which began production in 1840. The first regulation US musket made with a percussion lock was the US Model 1842, with production not beginning until 1844. Technically not a “musket”, the US Model 1841 rifle was the first muzzleloading American military arm produced with a percussion lock. The Hall breechloaders were percussion arms that pre-dated the 1841, but were not muzzleloaders.

2. The US Model 1855 two-band rifles also had a small iron patch-box, as did one of the later variations of the US Model 1855 rifle-musket. The patch-box was discontinued as superfluous beginning with the production of the US Model 1861s. For a more detailed explanation of the thought process which was well documented through archived correspondence, see Fuller, Claud E. The Rifled Musket “The Case for the Patchbox”. European military arms never have a patch-box and in the end it was simple economics more than any other factor that caused this practical and handy feature to be deleted from US military arms. Also, the “hook” type lock was typical of muskets produced before the mid-1850s and lacked a tumbler link. The mainspring of the lock rested on the tumbler itself.

3. Huddleston, Joe D. (1978). Colonial Riflemen in the American Revolution. George Shumway Publisher, York, PA. P. 11

4. Noe, David, Yantz, Larry W., and Whisker, James B, (1999). Firearms From Europe. Rowe Publications, Rochester, NY. P. 167

5. Steel is iron with the impurities (slag) removed, as distinguished from modern stainless steel which contains chromium and was not used in gun barrels until after1913.

6. Fuller, Claud E. The Rifled Musket, Stackpole Publishing Company, 1958. p. 198. In the end, Whitney produced about 29,000 additional contract arms, not including the 1841 rifles, during the Civil War years about 45% were for various state contracts, and 55% for the Federal government.

7. Phillips, H., Tyler T. Vermont Gunsmiths and Gunmakers to 1900. Privately published, 2000 (out of print)

8. American Precision Museum Windsor, Vermont, Special Exhibit: Celebrating the Crystal Palace Exhibit: From Robbins & Lawrence to Bauhaus. The Enfields produced from the Robbins & Lawrence contract were the so-called hard band P-53 with band springs and a swelled ramrod. The locks were marked "WINDSOR" with the date 1856.

9. Reilly, Robert M. U.S. Military Shoulder Arms 1816-1865. (1970). Andrew Mowbray Publishing Company.

10. Ibid; Note: Reilly identifies the first type adjustable sight used as the leaf type graduated to 900 yards, similar to the 1842 and early 1855 ladder types. The second type is a folding leaf with a screw type adjustment. There are also experimental types, as well as the two leaf sight similar to the Model 1861 musket sight that was widely used on rifles altered after 1859. Reilly goes into some detail on the alterations by Colt for sale to various units or states. He also states that between 1855 and 1860 8,879 rifles were altered in the National Armories. Hence, in the context of enlarging the caliber to .58 it seems that the addition of bayonet lugs, long range sights and increased caliber were not necessarily completed in identical numbers.

11. Williams, David. The Birmingham Gun Trade. Tempus Publishing, 2004 p. 72.

12. Ibid, Fuller.

13. Ever wonder why Colt's Special Model (also made by LG&Y) looks so much like a modified and polished P-53 Enfield? One possible reason is because the Robbins & Lawrence machinery from the British Enfield contract was used by Colt and LG&Y to produce the Special Model of 1861Ibid, Fuller

14. Steel is iron with the impurities (slag) removed, as distinguished from modern stainless steel which contains chromium and was not used in gun barrels until after1913.

15. Reilly, Robert M. U.S. Military Shoulder Arms 1816-1865. (1970). Andrew Mowbray Publishing Company.

16. The Italian reproduction of the Remington contract rifle, somehow nicknamed “Zouave”, is not historically accurate for any type of US Civil War enactment or living history. The original Remington 1862 contract rifles spent the Civil War years stored in Watervliet Arsenal, near Albany, New York and there is no record that they were ever issued to Civil War “Zouave” units or any other troops. The reproduction “Zouave” is often advertised as “a favorite of soldiers on both sides” however, there are no records which suggest this was the case.

17. Ibid, Noe Yantz

18. Ibid, Noe Yantz

19. 25,000 US 1841 rifles from Robbins & Lawrence and 20,000 from Remington, 22,500 from Whitneyville and 25, 296 from Harpers Ferry. This adds up to 92,296. There was also a small contract of 5,000 made by Tryon of Philadelphia, 1,000 of which were sent to Texas. Additionally there were Confederate copies of the US 1841 pattern being produced throughout the war by various southern contractors like Mendenhall, Jones & Gardner, J.P. Murray and Dixon, Nelson & Company. A rough estimate could be made at 100,000 arms, and if so in terms of arms in hand that puts the US 1841 rifle behind only the various US rifle-muskets, P-53 British Enfield, US 1816/22 and 1842 smoothbore muskets and the Austrian M-1854 Lorenz rifles, and all of the listed arms were considered “common”.

20. McAuley, John D. The Mississippi Rifle. American Rifleman, December 2002

NOTES

1. Meaning the Kentucky rifle, Pennsylvania rifle, Tennessee rifle…all designs which evolved from the German Yaeger (Jager) rifle.

2. The William Greener design was unique and did not use a cylindro-conical shape. The barrels of his rifled firearms (including his contract P53s) are stamped W GREENER INVENTOR of the EXPANSIVE BULLET, in case anybody might forget.

3. The Minié ball primarily used in the US Civil War was a later design modified by James H. Burton (Harpers Ferry) to do away with the iron plug in the base, instead utilizing a hollow base.

4. Fuller, Claud E. The Rifled Musket, Stackpole Publishing 1958, p. 16.

5. Meaning a company’s own design (like Sharps) not a commercially produced US model 1861, etc. Sharps continued to produce rifles with patch boxes well into the 1870s metallic cartridge-era, where “greased patches” were no longer in use (greased paper cartridge bullet patches so noted).

Regards,

Curt

Here is a monograph from the ill-fated 'Wearing of the Gray" Confederate compendium, about to be given life in the forth-coming "The Civil War Musket.... 2nd Edition."

The U.S. Percussion Rifle, Model 1841

By Craig L Barry and Curt-Heinrich Schmidt

By Craig L Barry and Curt-Heinrich Schmidt

US MODEL 1841 PERCUSSION RIFLE

Harpers Ferry, Eli Whitney, Robbins & Lawrence, and Remington

The early 1840s were still the era of the big bore .69 muskets with longer (42 inch) smoothbore barrels, still being turned out with flint locks (1). The US Model 1841 was a true rifle, with a shorter barrel (33”) bored to a smaller caliber (.54). The earlier military rifles had 33 ½” or 32 5/8” long barrels. This same length barrels were used on rifles of European manufacture, hence the 33” barrel was the unofficial “industry standard” of the time period. The rifle had a shorter barrel, was in a smaller calibre and answered the need for a rifle for light infantry and for special purposes. The US 1841 was the first regulation U. S. muzzle-loading rifle made in the percussion system. The barrel had a fixed rear sight and no provision for a bayonet. The US 1841 was a handsome arm with a large brass patch-box in the stock flat, a brass side plate opposite the lock assembly and brass barrel bands with iron band springs. The internal lock parts were the traditional flintlock style, with a hooked mainspring bearing directly on the tumbler. (2) The barrel was browned (not “armory bright”), the lock plate was case hardened and the ramrod was trumpet shaped with a brass tip. The US 1841 rifles were smaller in dimension but not lighter in weight, and at 9 3/4 lbs they were almost a full pound heavier than the standard US 1861 rifle-muskets and actually a few ounces heavier than the much larger and longer US Model 1842 percussion muskets. The modern reproduction of the US 1841 is one of the few reproductions not substantially heavier than the original firearm. It actually weighs about the same. The nickname most often associated with the US 1841 was the “Mississippi Rifle” due to a Congressman from that state named Jefferson Davis. As a reward for Congressman Davis’s vote on a tariff bill, President James Polk arranged for the 1st Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (“The Mississippi Rifles”) that “Colonel” Jefferson Davis had recruited for the Mexican War to receive US 1841 rifles. Thanks in part to the effective fire of the 1st Mississippi regiment at Buena Vista, Mexico in February of 1847, Davis was able to hold back several attacks by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna on the American force and the Mexican army subsequently retired from the field. Davis, wounded in the action, returned home in June of 1847 to go on to become a senator from the state of Mississippi, Secretary of War, and later President of the Confederacy. Other period nicknames for the US 1841 rifle include “Harpers Ferry rifle,” “Whitney rifle,” “Jaeger rifle” variously misspelled as “Yaeger” or “Yager”, and “Windsor rifle.” This most-often nicknamed rifle produced by the three large government contractors (and the United States Harpers Ferry Armory) has an interesting and important role in Civil War history and one that used to be overlooked by the Civil War historical community.

Background

“Whatever state shall thoroughly comprehend the nature and advantages of rifled barrel pieces, and, having facilitated their construction, shall introduce into their armies their general use, with a dexterity in the management of them, they will by this means acquire a superiority, which will almost equal

anything that has been done at any time by the particular excellence of any kind of arms.”

anything that has been done at any time by the particular excellence of any kind of arms.”

-Benjamin Robbins, 1747 (3)

As early as the First War for American Independence, General George Washington observed that the dress of the rifleman where possible must be maintained to “…carry no small terror to the enemy, who think every person a complete marksman.” (4)

While the major battles of the Revolutionary War of 1776 were fought on the East Coast very similar to European standards of engagement, the rifleman was quite different from the average American Colonist. While life in the Tidewater regions of the East Coast was almost equal to that in Britain, life on the plateau and mountains of the frontier was distinct. The individual frontiersman was required to defend his cabin, livestock, and cleared land from wildlife and hostile Indians. When combined with measures of self-reliance, independence, pragmatic brutality, hardship, deprivation, and a sense of democracy and familiarity with violence, riflemen were destined to have an impact in any war.

With the Contract Rifle of 1792, the U.S. Model 1803 Rifle, the Contract Rifles of 1807, 1814, and 1817, and the Contract Rifles of 1819 (Hall’s Patent), the day of the rifleman had arrived. With the advent of the new .58 “minie” rifle in 1855, adding greater effective firing range and accuracy to the rifle, advances and developments first begun by the British, French, and Americans during the Napoleonic War era led to (then) Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to look toward revisiting the “exercise and maneuvers” of troops acting as light infantry or riflemen. Davis was aware of the studies done in Europe to revise weapons and tactics, and appointed several officer boards to observe them and suggest changes to the U.S. system which was based upon the 1835 manual done by General Winfield Scott. Davis looked to Brevet Lt. Colonel William Hardee of the 2nd Dragoons who had studied tactics at the French cavalry school at Saumur in 1841, and where he had picked up French innovations regarding the value of rapid movement and deployment, the value of skirmishers, and hit-and-run style tactics by light infantry based upon French Legionnaire experiences in Algeria in the 1830s.

U.S. Model 1841 Percussion Rifle

While a number of the U.S. Breechloading Flintlock Rifle Model 1819 (Hall’s Patent) were converted to percussion, and the rifle updated as a percussion version in the form of the U.S. Breechloading Flintlock Rifle Model 1841, the decision to produce percussion rifles and muskets led to a new design in 1841. The US 1841 Rifle was stocked in hard oiled finished Pennsylvania grown American Black Walnut and brass mounted, weighing nine pounds twelve ounces, with an overall length of 48 ½ inches. The lacquer brown .54 calibre barrel was 33 inch long with seven grooves and a (slow) 1:72 inch twist. The 5 ¼ inch lock plate was flat with beveled edges, and the plate and hammer were color case hardened by quenching with the lock plate being inlet into the stock to bevel height. All furniture was polished brass, with the barrel secured by two band springs which held brass bands, the upper one being doubled looped and 2 9/16 inches long on top and 3 ¼ inches long on the bottom. Both straps are 15/32 inches wide. Screws and sling swivels were oil quenched blackened. The barrel carried the inspected, proofed, and acceptance (“V,” “P,” and “Eaglehead”) stamps, as well as a date usually that matched the lock plate date on the 2 1/16 inches long tang. Some contractor made barrels were stamped ‘STEEL.” The stock was marked with an inspector’s cartouche opposite the lock in the round or oval styles of the 1840’s or the square or rectangular styles of the 1850’s. A simple brass blade served as a front sight was set 13/16 inches form the muzzle, and the non-adjustable rear sight was a simple “v” notched block in the “Pennsylvania/Kentucky” rifle tradition. Surprisingly the sights were dead set for fifty yards. The brass trigger plate was nine inches long with rounded ends, holding a blued trigger on a lug. A separate brass trigger guard (bow) was attached with two spanner nuts. The 4 3/8 inch brass flat butt plate is stamped with a small “US” to the rear of the upper tang screw. The 32 ¾ inch bright steel ramrod and had a 23/32 inch long brass trumpet or flared shaped tip with a concave front for loading round balls. A “spoon” device in the stock channel secured the brass tipped ramrod.

A distinctive feature of the US 1841 Rifle was its large brass “patch-box” or implement box that measured 7 5/8 inches by 1 11/16 inches. The bottom of the patch-box mortise typically carried one large very shallow circular cut centered with sometimes two others faintly visible on the side with a shallow hole in the centers, the remnants of the bit used to make the depth cut of the mortise. The bottom front end of the mortise was also drilled out to hold the space cone. Inside of the implement box were carried the three appendages that made up the US 1841 Rifle’s tools, on top a wiper with a long shaft, in the center the US 1841/1842 Combination tool (cone wrench with a single screwdriver arm), and on the bottom a ball screw on a shorter shaft to allow it to fit next to the cone. When all three tools and spare cone were carried, there was little room for anything in the box. Most tools were contractor made and were japanned black or oil quenched blackened carrying stamps such as “S,” “M,” or large “US.” Springfield and Harpers Ferry made tools have a grayish blue finish and have a small ‘US” stamped on them.

There was no provision to mount a bayonet, and at times the rifle was augmented by the M1836 Hicks or the M1849 Ames “Rifleman” knife. The lock plate was stamped with the name of the maker in one or two vertical lines over the year to the rear of the hammer, and for those made at Harpers Ferry Armory, a spread eagle and “U.S.” to the front of the hammer. The US Model 1841 percussion rifle used a cartridge containing a pre-patched .535 round ball and 75 grains of powder. The US1841 Rifle would have a profound influence on the new .58 calibre Model 1855 rifle, which incorporated both the new .58-minie bullet as well as the Maynard tape primer system. The first two variations (of five) of the US 1855 Rifle, made in 1857 and then modified in 1858, were brass mounted like the US 1841.

In addition to the 1st Mississippi, the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, organized during the Mexican War also carried the US 1841 rifle in Mexico and later on their march from Fort Leavenworth to Oregon along with Colt revolvers and some Maynard carbines. Production of the US 1841 rifle did not begin at the US Armory until 1846 when 700 were turned out at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Between 1846 and the end of production in 1855, 25,296 rifles were produced at Harpers Ferry. There is some controversy over production at Springfield Armory divided between camps that there are no records indicating any production of US 1841 rifles and others that 3,200 were produced in 1849. Springfield records are somewhat unclear, and the 3,200 referenced in the “3,200 arms” would appear not to be US 1841 rifles but rather shortened US 1842 muskets altered for the Fremont Expedition. However, from time to time, US 1841 rifles are found with Springfield marked lock plates (see pictures). While some argue these are actual Springfield produced US 1841 rifles, others believe that these rifles were refurbished or retrofitted with Model 1847 Musketoon locks or lock plates which are close to identical to the US 1841 lock. It is worth noting that any US 1841s produced at Springfield Armory would be exceedingly rare whatever the case, as Springfield did not produced muzzle-loading rifles like the US 1855 either, only the longer three band rifle-musket. Harpers Ferry Armory made the US model rifles. The reasons for this division of manufacture are not documented.

"Steel" stamped barrel:

A Look at US 1841 Percussion Rifle Armory and Contract Alterations

HARPERS FERRY ARMORY

In the mid-1700s Robert Harper, a millwright formerly from near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania moved to Virginia and operated a ferry service across the gap in the Blue Ridge where the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers converge. In 1763, the Virginia General Assembly established the town of “Shenandoah Falls at Mr. Harper’s Ferry.” In 1796, the Federal government purchased the 125-acre parcel of land bounded by the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers from the heirs of Robert Harper. Construction of the "United States Armory and Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry" began in 1799. Three years later full-scale production of arms began. Muskets, rifles and, after 1805, pistols were all manufactured here. Total production until the outbreak of the Civil War (and abandonment of the Armory) exceeded 600,000. (5)

Captain John H. Hall, beginning in 1819 built the Hall Carbine at Harpers Ferry on the principle of interchanging parts and using an assembly line process. The Hall Carbine had a removable breech section and lock unit. When the Federal government adopted the Hall Carbine, the United States became the first nation to employ a breech-loading weapon as a “standard” military arm. Originally produced in flint, the Hall Carbine evolved into a percussion version as well and remained in service for almost fifty years.Harpers Ferry also produced 25,296 US Model 1841 Percussion rifles at the Armory between 1846 and 1855. There is no evidence that the US 1841 was produced at Springfield Armory. The period nickname for the US 1841 of “Harpers Ferry Rifle” is somewhat confusing as the US Model 1855 two-band rifle shared the same nickname in period accounts.

The Harpers Ferry US Model 1841 barrels are marked with a “VP” and eagles head at the rear of the breech, and besides lock plate markings are distinct for having no cartouches opposite the lock. The initials JLR or JHK often appear in block letters in the area where the cartouche would be expected. The patch-box has three small router holes and no “U.S” initials on the butt plate. (6)

US 1841 “Harpers Ferry Rifle”

Harpers Ferry Alterations

The Americans were not entirely without vision when it came to the concept of the changing round ball being looked at in Europe by some men as with Delvigne, Pontchara, Thierry, Thouvenin, and Minie in France, Augustin in Austria, and Metford, Pritchett, and Wilkinson in Britain. Between 1853 and 1855, at Harpers Ferry and Springfield Armories, small arms projectile tests were conducted. In late 1853 Colonel Benjamin Huger was authorized by the Ordnance Department to conduct tests at Harpers Ferry. Tests of the Minie system led to James Burton, acting Master Armorer at Harpers Ferry, to come up with different ideas for expanding the base of the conical ball to grip the rifling of a barrel.. A prototype .69 and .54 bullet based upon the Minie design was chosen. Additional experiments were ordered done at Harpers Ferry in October of 1854 under Lt. J. G. Benton based upon the Pritchett bullet. Another series of tests under Benton were authorized in the spring of 1855 at Springfield Armory. After the tests, Colonel H. K. Craig recommended to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis that a new bullet in .58 calibre be proposed for small arms. The proposal was accepted by Davis in July of 1855, and Davis called for the establishment or alteration of a .69 rifle-musket altered from smoothbore, a new .58 rifle-musket, a new .58 rifle, an altered M1841 rifle from .54 to .58, and a new .58 pistol-carbine. The M1855 Carbine, authorized in 1854 in .54 would also be updated to .58.

Somewhat anticipating the development of the new bullet, in late 1854 and early 1855, Harpers Ferry re-tooled the M1841 Rifle as its potential for long range firing with the new .54 “minie” ball was hampered by its limited fixed sights. 9,800 M1841 rifles were altered by Harpers Ferry to fire minie ball ammunition. Several variations are known, the key differences being .54 or .58, and several different forms of the long range rear sight graduated to 900 or 1,000 yards- one a slightly larger version that was soldered to the barrel and the other the M1855 Rifle long range rear sight that was dovetailed and screwed to the barrel. With the advent of the short-range M1855 Rifle rear sight in late 1858 graduated to only 100, 300, and 500 yards, Harpers Ferry altered M1841’s carried the new rear sights. In late 1854 and early 1855, Harpers Ferry Armory altered 1, 631 rifles to take the new “screw” long range rear sight designed by Benton and 1,649 rifles to take the 1,000 and 900 yard high-hump or “roller coaster” sliding pattern ladder rear sights. These long range sighted US 1841 rifles were also modified to accept sword bayonets typically by replacing the long front band/nose cap with a shorter version, replacing the brass front sight blade with an US 1855 Rifle front sight, adding an US 1855 bayonet lug to the barrel for either a special “US 1841” type sword bayonet or the US 1855 Rifle sword bayonet, and replacing the flared concave faced brass tipped ramrod with an all iron/steel one with a tulip type cupped head. With the adoption of the .58 minie bullet in July of 1855, the Armory reamed the bore from .54 to .58 as well. About 1,646 "Snell" type bayonets were produced at Harpers Ferry in 1855 that used a rotating thumbscrew type lock that required two small cuts on the side of the barrel to engage. Between 1855 and 1857 Harpers Ferry produced 10,286 sword bayonets to be used with a more conventional side mounted lug, but these required that the M1841 rifle stocks be cut back slightly and a shortened upper band fitted. Later, a third type of bayonet was produced under contract that required no alteration to the rifle, only the addition of a bayonet lug that clamped in place. The presumption has been that a comparable number of rifles were altered for the bayonets in the context of enlarging the caliber, but that is not the case. The numbers do not jibe. In 1855, the first of the altered M1841’s were issued to the 2nd, 6th, and 10th U.S. Infantry. Some of these altered rifles were issued to Regular infantry regiments as early as 1856, followed by the largest issuances of 5,600 altered rifles in 1858 to the Artillery, and Mounted Rifles, and Dragoons at various posts.

ROBBINS & LAWRENCE

Samuel Robbins and Richard Lawrence came to the gun trade much later than either Eli Whitney or Remington, and left sooner. Located on the Connecticut River in an area known as “Precision Valley” for the amount and quality of machine tools, Robbins and Lawrence entered into a partnership with Nicanor Kendall building rifles at Windsor Prison in 1844 actually employing prisoners as cheap labor. Probably realizing the risks and limitations involved with making and storing firearms in a prison, the partners built a large brick factory two years later in 1846. Frederick Howe was then the factory superintendent. Howe, who would later be hired away by Providence Tool, invented several new milling machines and lathes for the making of interchangeable gun parts by Robbins & Lawrence. Their first contract with the US government was to produce copies of the US Model 1841 percussion rifle. The very first US 1841s produced by the firm on contract were marked with all three names, Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence. These have the earlier lock plate dates. After 1847 when Nicanor Kendall left, the firm changed names and the locks were simply marked Robbins & Lawrence over US, with the date and WINDSOR behind the hammer (7). The barrel flat on the Robbins & Lawrence US 1841 was not marked STEEL, as were all the Remington and some of the Whitneyville variants. The government US 1841contracts totaled 25,000 US 1841 rifles and all were delivered by 1855.

Robbins & Lawrence received global attention in England at the 1851 Crystal Palace exhibition (a "World's Fair" of sorts). Their display was very simple, consisting of six rifles which were disassembled and reassembled to demonstrate interchanging of parts. At the time military arms in Britain were hand-made from parts not likely to

interchange with another gun, much less six others. The British government took note, and sent a commission to Windsor, VT resulting in a major contract for Robbins & Lawrence to supply 25,000 (type 2) P-53 Enfields to the Crown during the Crimean War as well as machinery and tools for the refurbishing of the Royal Small Arms Manufactury at Enfield Lock (8). The British contract proved their undoing. Plagued by production problems from the beginning and burdened by debt from re-tooling, Robbins & Lawrence could only deliver 10,500 on the original P-53 Enfield contract by September 1856. By then the Crimean War was over, and the British foreclosed on the contract (9). In addition, the company had recently lost over $100,000 (a princely sum in those days) on a bad investment building railroad cars. Robbins & Lawrence were forced to liquidate their assets. Ironically, Colt, Eli Whitney and LG&Y were all beneficiaries purchasing manufacturing equipment and machinery that they later used to produce contract rifle-muskets during the Civil War for the Federal government (10). Robbins & Lawrence US 1841 rifles were mostly stored at Watertown Arsenal near Boston prior to alteration.

US 1841 “Windsor Rifle” (Robbins & Lawrence) here shown with later alteration that included an M1855 "short range" rear sight:

WHITNEYVILLE

The private Armory, as Whitney called it, was divided into two main facilities on opposite sides of the Mill River. On the East side was the facility for the shaping of metal parts and on the west bank was the machinery for the cutting of parts and shaping of wood (11). Eli Whitney passed away in 1825, and some time later as previously stipulated his only son, Eli Whitney, Jr. took over the operation of the Whitneyville Armory. The first government contracts procured by Eli, Jr. were for the “new” US Model 1841 Percussion Rifle, actually four contracts from 1842 to 1854, for a total production of 22,500.

The Federal contracts specified “parts interchangeability” and the US government performed random inspections on each shipment to determine if the rifles were military gauged. Many were not accepted and by the mid-1850s Whitneyville found itself with a large inventory of “reject” parts. Whitney preferred state contracts, which were not subject to inspection with gauges (12). Whitneyville also produced commercial US 1841s out of condemned and surplus parts from Springfield and Harpers Ferry which were sold to state militia. The Whitney Militia Rifle is a hybrid between a US 1841 rifle and a Model 1855 rifle with a “hump” type lock plate, minus the patch-box, tape primer and using a Maynard type hammer. Two types of the Militia Rifle were produced with the main difference being the location of the rear sight. Type I has a ladder type long range sight located 2 7/8 inches from the breach while the Type II has the sight about 6 inches down the barrel.

Whitney is most famous for what was termed “good and serviceable arms not subject to government inspection of gauges” an interesting strategy for the enterprise that started the whole “American Plan” of parts interchangeability. The civilian and to an extent the state militia markets did not support the need for strict interchangeability of parts, as long as the rifles were functional and would fire reliably. However, Whitneyville’s use of condemned parts (the Armory would strike over the government condemnation marks) to fob off guns of lesser quality to unsuspecting buyers is in contrast to the efforts of other U.S. commercial gun-makers. To Whitney, the cheapest route was always favored.

The US 1841 rifles were generally marked “E. Whitney”over “US” with “N. Haven” and the date behind the hammer (13). The barrels were sometimes marked STEEL on the barrel flat. They were also sometimes marked “U.S.” over SK, GW, JH, JCB, JPC, or ADK over VP. There were two cartouches opposite the lock.

US 1841 (later contract) made by Whitney, use by Colt for his alterations. Note Colt M1855 Revolving Rifle rear sight.

E. REMINGTON & SONS