Confederate Brass Framed revolvers: Myths and Realities, Part 2.

The Griswold & Gunnison, aka Griswold and Grier, aka the Griswold, aka the Griswoldville, aka the Confederate Brass Colt, aka the Round Barreled Navy revolver.

Thirty-two year old Samuel Griswold of Windsor, Connecticut migrated to Clinton, Georgia in 1822 with his family. Samuel found a job clerking in a store, and his wife tool in tailoring work while he put together the beginnings of a cotton gin making business capitalizing on machinery knowledge he had gleaned in Windsor.

Forming a partnership with Daniel Pratt, a transplanted New Hampshire man, Griswold and Pratt set up a small facility for the making of cotton gins, but hedged their bets by adding a saw mill and grist mill as well. Soon after, Pratt left, heading to Alabama where he founded his own town of Prattville and later designed the state capitol building in Montgomery.

Business was good, and when surveyors came in 1835 to plan out the route of the Central Railroad of Georgia, Griswold was able to snatch up 4,000 acres on the right-of-way about nine miles north of Macon. There he established his own town of Griswoldville complete with a mansion, homes for his children, a church, stores, gin factory, post office, a foundry, a planning mill, saw and grist mills, a soap, tallow, and candle factory, and a laundry. Plus more than fifty houses and cottages for his workers and more than 100 slaves.

In February 1862, Georgia governor Brown made an appeal for “Georgia pikes’ hoping that patriotism and $5 bonus per delivered pike would do the trick. As others did as well, Griswold combined patriotism and a chance for profit, and converted his gin factory over to a pike factory with the help of E. Grier of Grier & Masterson. Over the next two months, Griswold would make 804 pikes.

The Spring of 1862 saw a serious threat from the Federals on Savannah, and Colonel (later General) Josiah Gorgas feared that the considerable Confederate ordnance stores there would be lost if not moved. It was decided that Macon would do well, being some 180 miles inland and about to become one of the largest ordnance centers. Gorgas ordered the officer in charge at Savannah, Captain Richard Cuyler, to supervise the move.

About that time, Samuel Griswold had the idea that if he could make pikes, he could make Colt Navy revolver copies and approached the Confederate government for a contract to do so. He formed a partnership with Arvin Nye Gunnison his business agent and warehouse manager in New Orleans since 1858.

His timing was good, and corresponded to an effort by the Confederacy to ramp up arms production to meet their critical need of being short of weapons.

In May of 1862 Gorgas wrote to Cuyler that he was authorized to accept from the new company of Griswold and Gunnison as many revolvers as they could deliver in eight months at the price of $40 each.

But Griswold had the house before the cart, and was not yet set up to start production. He wrote back saying within two months they could have a sample, and from there expected to turn out 50-60 revolvers per week.

It would be a slow start, plagued by similar problems many of the would-be Confederate gun makers would experience- a lack of machinery, a lack of raw materials especially iron or steel, skilled workers and armorers. Superintendent of the new Macon Armory, Walter Hodgkins stopped by in July to proof cylinders and barrels, and found that Griswold and Gunnison new operation had about 100 pistols underway in a factory housing 22 machines operated by 24 workmen, 22 of which were slaves.

The proof did not go that well. Recommendations were made and in August another round of proofings were conducted and cylinders and barrels passed as “sufficient.”

The first batch of 25 revolvers were completed In July but for some reason not sent through the system until October, when 22 were submitted for inspection and proof of 54 grains of powder and two balls, and cylinders filled with powder and one and two balls . 18 passed, with three failing due to burst barrels and one burst cylinder. One failed for a broken loading lever catch. Other problems were cited such as poor hardening and or tempering of parts, springs that were too short, and a ratchet that was too short to work the action.

In October, Griswold had increased his workforce up to 30 Black slaves, but suffered the loss of the 5-6 skilled armorers into the army. ‘Good judges’ deemed the “Negroes” to be “fair mechanics.”

From the start shortages of iron ad steel slowed production, as well as bronze. Priority shipments of iron were authorized, as well as bronze being secured through the famous church bell drive for churches to “loan” their bells to the War effort. Once an adequate supply of raw materials was forthcoming, Griswold and Gunnison were able to turn up production to a consistent 135 revolvers month or roughly five per day:

1862.

July……..……….25

August…………75

September…..80

October……….100

November……105

December…….120

1863. January through December…. 135 per month

1864. January through November… 135 per month.

TOTAL: 3,500 (Highest known serial number is 3606 though)

On November 1, 1864 Sherman occupied Atlanta and Macon was threatened. Samuel Griswold saw the writing on the wall, and wrote to Colonel Burton at the Macon Armory that he did not want t own the pistol factory any longer and preferred the Confederate to either lease or buy the factory and the slaves. Burton then wrote to Gorgas that he opposed taking over the factory, but rather Griswold might be enticed to change his mind if they paid more for the revolvers.

But on November 11th, Sherman started his move from “Atlanta to the Sea.” As the Federal right wing of the Army of the Tennessee advanced, a mixed force of Georgia Home Guards, the Rigdon Guard of Augusta, and a militia force of Griswoldville militiamen put up a spirited defense and the initial attack on Macon was held off at a hill about a mile east of town.

On November 21st, Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry raided the town capturing a supply train, burning the train station, and some buildings. The main force arrived on the 22nd, and after another spirited defense greatly hampered by lack of artillery and cavalry, the Confederates were forced to withdraw. Kilpatrick destroyed the Griswold and Gunnison factory. Most of the town was burned.

And that ended pistol production at Griswoldville.

On March 21, 1865 Burton wrote to then Colonel Cuyler asking for his cooperation in getting Gunnison back in the revolver making business. Nothing came of it, and on March 31, 1865 Burton wrote to the revolver company of Rigdon & Ansley informing them they were placed under his charge.

In less than two weeks, Lee surrendered.

For years, farmers farming the area unearthed revolver parts, and surface prospectors turned up parts such as steel dies, barrels, cylinders, hammers, triggers that were rejects or unfinished parts. And, includes an iron frame, possibly a prototype or sample.

Griswold & Gunnison revolvers are known in two types. The early production Type 1 has a rounded barrel housing (rear end) while the later production (roughly post #3000) Type II has a more “dragoon” style octagonal one.

Twisted iron cylinders are common. Depending on the alloy at the time of use, the brass frames can be yellow brass (gun metal bronze) or red brass depending on the mix of tin and copper.

External workmanship is good, however internal parts can be functional but not finished and contain many scratches and gouges left in place as not a concern.

Serial numbers go up to four digits, all being hand stamped one at a time and so are “crooked’ and uneven.

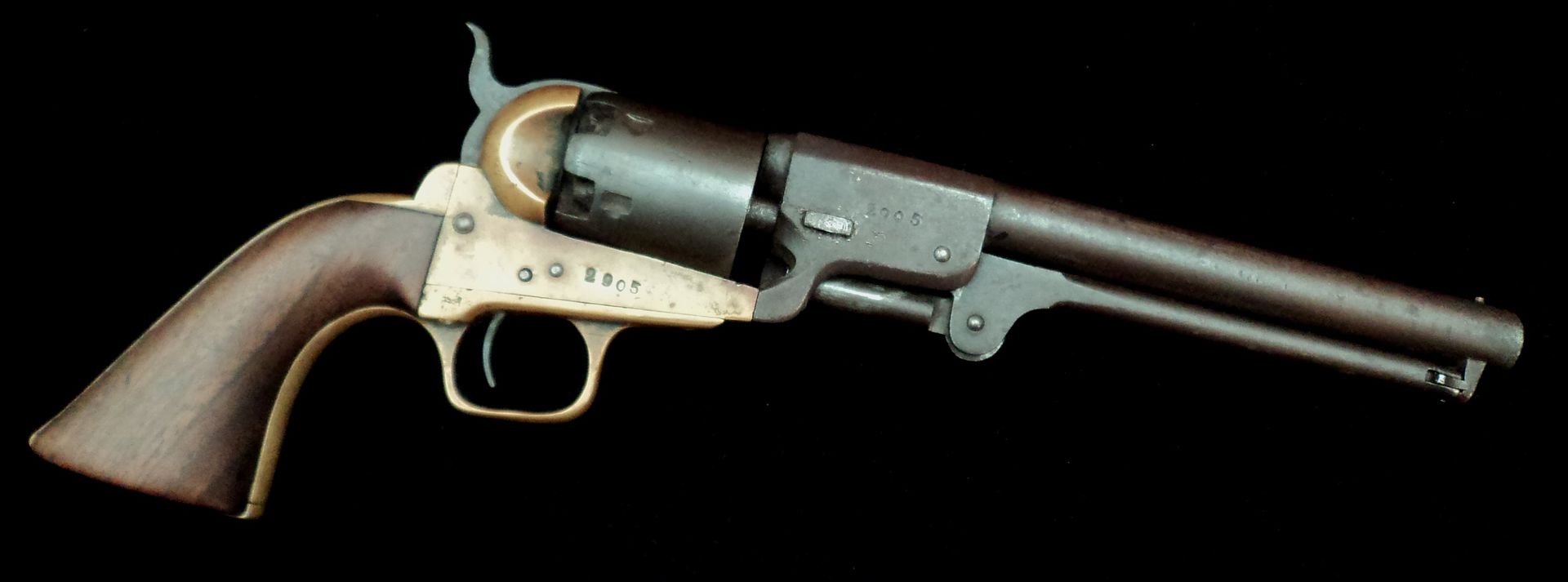

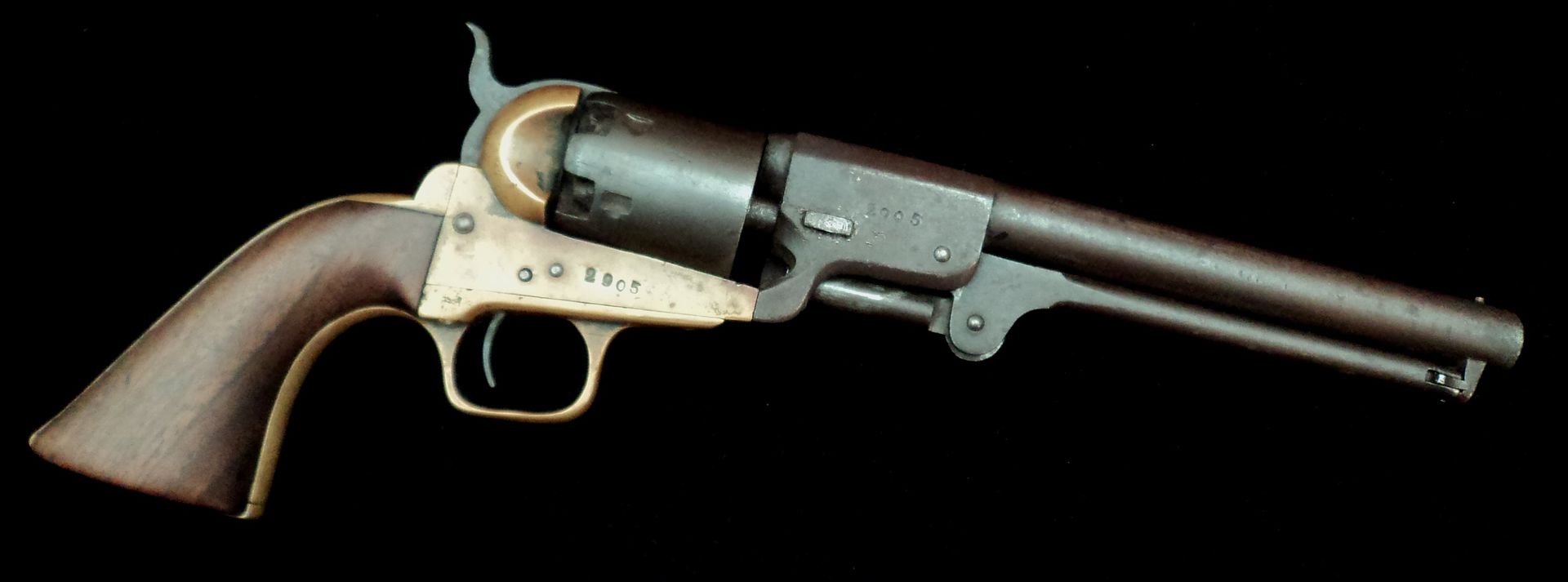

Type I:

Type II:

Reproductions.

The reproduction of the Griswold and Gunnison revolver goes all the way back to 1957 and the start of the reproduction firearm industry in Italy through Val Forgett, Sr., Vittorio Gregorelli, and the Brescia Italy firearms industry. While the first would be a copy of the Colt M1851 Navy (named the “Yank”), its brother would be the Griswold and Gunnison (named the “Reb” or sometimes the “Reb 60” or sometimes the “Reb 1860.”

The repro of the G & G is a Type II, post July 1864 production. At the moment I do not recall if there is a Type I repro or not.

As with all Italian reproductions, it suffers from the usual litany of wrong grip wood, wrong metal finishes. Its biggest fault is perhaps that it uses a copy of the Colt M1851 Navy grip frame reproduction that does not angle as much as the original.

Here is an “antiqued” G & G Type II with simulated twisted iron cylinder. The serial number, unfortunately is in the very early Type I range:

Here it shows well the faceted flats of the dragoon style barrel end of the Type II’s:

And another "aged" one"

References:

Albaugh, William, A. III, The Confederate Brass-Framed Colt & Whitney. Broadfoot Publishing Company, Wilmington, NC. 1955

Albaugh, William, A. III, Benet, Hugh. Jr, Simmons, Edward. Confederate Handguns. George Shumway, Publisher, York, PA. 1963

Curt

The Griswold & Gunnison, aka Griswold and Grier, aka the Griswold, aka the Griswoldville, aka the Confederate Brass Colt, aka the Round Barreled Navy revolver.

Thirty-two year old Samuel Griswold of Windsor, Connecticut migrated to Clinton, Georgia in 1822 with his family. Samuel found a job clerking in a store, and his wife tool in tailoring work while he put together the beginnings of a cotton gin making business capitalizing on machinery knowledge he had gleaned in Windsor.

Forming a partnership with Daniel Pratt, a transplanted New Hampshire man, Griswold and Pratt set up a small facility for the making of cotton gins, but hedged their bets by adding a saw mill and grist mill as well. Soon after, Pratt left, heading to Alabama where he founded his own town of Prattville and later designed the state capitol building in Montgomery.

Business was good, and when surveyors came in 1835 to plan out the route of the Central Railroad of Georgia, Griswold was able to snatch up 4,000 acres on the right-of-way about nine miles north of Macon. There he established his own town of Griswoldville complete with a mansion, homes for his children, a church, stores, gin factory, post office, a foundry, a planning mill, saw and grist mills, a soap, tallow, and candle factory, and a laundry. Plus more than fifty houses and cottages for his workers and more than 100 slaves.

In February 1862, Georgia governor Brown made an appeal for “Georgia pikes’ hoping that patriotism and $5 bonus per delivered pike would do the trick. As others did as well, Griswold combined patriotism and a chance for profit, and converted his gin factory over to a pike factory with the help of E. Grier of Grier & Masterson. Over the next two months, Griswold would make 804 pikes.

The Spring of 1862 saw a serious threat from the Federals on Savannah, and Colonel (later General) Josiah Gorgas feared that the considerable Confederate ordnance stores there would be lost if not moved. It was decided that Macon would do well, being some 180 miles inland and about to become one of the largest ordnance centers. Gorgas ordered the officer in charge at Savannah, Captain Richard Cuyler, to supervise the move.

About that time, Samuel Griswold had the idea that if he could make pikes, he could make Colt Navy revolver copies and approached the Confederate government for a contract to do so. He formed a partnership with Arvin Nye Gunnison his business agent and warehouse manager in New Orleans since 1858.

His timing was good, and corresponded to an effort by the Confederacy to ramp up arms production to meet their critical need of being short of weapons.

In May of 1862 Gorgas wrote to Cuyler that he was authorized to accept from the new company of Griswold and Gunnison as many revolvers as they could deliver in eight months at the price of $40 each.

But Griswold had the house before the cart, and was not yet set up to start production. He wrote back saying within two months they could have a sample, and from there expected to turn out 50-60 revolvers per week.

It would be a slow start, plagued by similar problems many of the would-be Confederate gun makers would experience- a lack of machinery, a lack of raw materials especially iron or steel, skilled workers and armorers. Superintendent of the new Macon Armory, Walter Hodgkins stopped by in July to proof cylinders and barrels, and found that Griswold and Gunnison new operation had about 100 pistols underway in a factory housing 22 machines operated by 24 workmen, 22 of which were slaves.

The proof did not go that well. Recommendations were made and in August another round of proofings were conducted and cylinders and barrels passed as “sufficient.”

The first batch of 25 revolvers were completed In July but for some reason not sent through the system until October, when 22 were submitted for inspection and proof of 54 grains of powder and two balls, and cylinders filled with powder and one and two balls . 18 passed, with three failing due to burst barrels and one burst cylinder. One failed for a broken loading lever catch. Other problems were cited such as poor hardening and or tempering of parts, springs that were too short, and a ratchet that was too short to work the action.

In October, Griswold had increased his workforce up to 30 Black slaves, but suffered the loss of the 5-6 skilled armorers into the army. ‘Good judges’ deemed the “Negroes” to be “fair mechanics.”

From the start shortages of iron ad steel slowed production, as well as bronze. Priority shipments of iron were authorized, as well as bronze being secured through the famous church bell drive for churches to “loan” their bells to the War effort. Once an adequate supply of raw materials was forthcoming, Griswold and Gunnison were able to turn up production to a consistent 135 revolvers month or roughly five per day:

1862.

July……..……….25

August…………75

September…..80

October……….100

November……105

December…….120

1863. January through December…. 135 per month

1864. January through November… 135 per month.

TOTAL: 3,500 (Highest known serial number is 3606 though)

On November 1, 1864 Sherman occupied Atlanta and Macon was threatened. Samuel Griswold saw the writing on the wall, and wrote to Colonel Burton at the Macon Armory that he did not want t own the pistol factory any longer and preferred the Confederate to either lease or buy the factory and the slaves. Burton then wrote to Gorgas that he opposed taking over the factory, but rather Griswold might be enticed to change his mind if they paid more for the revolvers.

But on November 11th, Sherman started his move from “Atlanta to the Sea.” As the Federal right wing of the Army of the Tennessee advanced, a mixed force of Georgia Home Guards, the Rigdon Guard of Augusta, and a militia force of Griswoldville militiamen put up a spirited defense and the initial attack on Macon was held off at a hill about a mile east of town.

On November 21st, Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry raided the town capturing a supply train, burning the train station, and some buildings. The main force arrived on the 22nd, and after another spirited defense greatly hampered by lack of artillery and cavalry, the Confederates were forced to withdraw. Kilpatrick destroyed the Griswold and Gunnison factory. Most of the town was burned.

And that ended pistol production at Griswoldville.

On March 21, 1865 Burton wrote to then Colonel Cuyler asking for his cooperation in getting Gunnison back in the revolver making business. Nothing came of it, and on March 31, 1865 Burton wrote to the revolver company of Rigdon & Ansley informing them they were placed under his charge.

In less than two weeks, Lee surrendered.

For years, farmers farming the area unearthed revolver parts, and surface prospectors turned up parts such as steel dies, barrels, cylinders, hammers, triggers that were rejects or unfinished parts. And, includes an iron frame, possibly a prototype or sample.

Griswold & Gunnison revolvers are known in two types. The early production Type 1 has a rounded barrel housing (rear end) while the later production (roughly post #3000) Type II has a more “dragoon” style octagonal one.

Twisted iron cylinders are common. Depending on the alloy at the time of use, the brass frames can be yellow brass (gun metal bronze) or red brass depending on the mix of tin and copper.

External workmanship is good, however internal parts can be functional but not finished and contain many scratches and gouges left in place as not a concern.

Serial numbers go up to four digits, all being hand stamped one at a time and so are “crooked’ and uneven.

Type I:

Type II:

Reproductions.

The reproduction of the Griswold and Gunnison revolver goes all the way back to 1957 and the start of the reproduction firearm industry in Italy through Val Forgett, Sr., Vittorio Gregorelli, and the Brescia Italy firearms industry. While the first would be a copy of the Colt M1851 Navy (named the “Yank”), its brother would be the Griswold and Gunnison (named the “Reb” or sometimes the “Reb 60” or sometimes the “Reb 1860.”

The repro of the G & G is a Type II, post July 1864 production. At the moment I do not recall if there is a Type I repro or not.

As with all Italian reproductions, it suffers from the usual litany of wrong grip wood, wrong metal finishes. Its biggest fault is perhaps that it uses a copy of the Colt M1851 Navy grip frame reproduction that does not angle as much as the original.

Here is an “antiqued” G & G Type II with simulated twisted iron cylinder. The serial number, unfortunately is in the very early Type I range:

Here it shows well the faceted flats of the dragoon style barrel end of the Type II’s:

And another "aged" one"

References:

Albaugh, William, A. III, The Confederate Brass-Framed Colt & Whitney. Broadfoot Publishing Company, Wilmington, NC. 1955

Albaugh, William, A. III, Benet, Hugh. Jr, Simmons, Edward. Confederate Handguns. George Shumway, Publisher, York, PA. 1963

Curt

Comment